What is your pathway to tolerance and empathy?

At Sound Potential, our work focuses on music and the arts as a way to generate tolerance and empathy – qualities that are more important than ever in a world where racism and prejudice continue to profoundly impact people’s lives. In this series, we are asking people from many walks of life to reflect on what tolerance and empathy means to them.

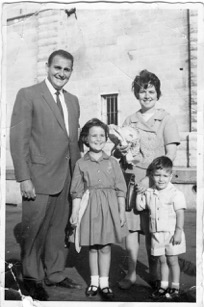

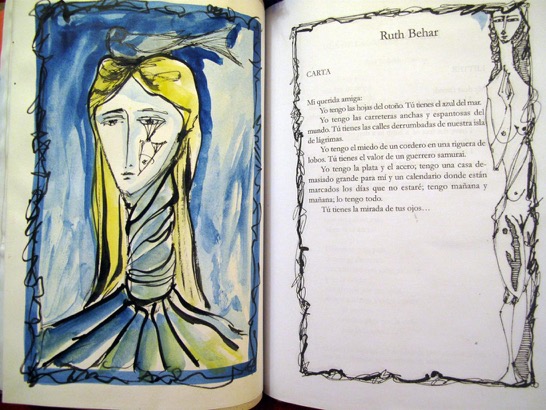

Our first dispatch comes from cultural anthropologist and author Ruth Behar, who sat down with our executive director Natasha Zaretsky in Mexico City to talk about her prolific body of creative and scholarly work, including her first middle grade novel, Lucky Broken Girl, a documentary film about Cuba, Adio Kerida, and her academic scholarship.

Here, Ruth shares her reflections on the significance of immigration, vulnerability, reading, and music to her personal pathways to empathy and tolerance. As an anthropologist, her work builds on concepts central to tolerance and empathy – including the relationship between self and other, the ethics of observation, and how to connect across differences—all themes Ruth touched on in our discussion. But her pathways to tolerance and empathy began for her much earlier, as a child, rooted in the struggle for belonging.

An Immigrant Child

Natasha Zaretsky: Much of what we’re doing at Sound Potential focuses on the power of music and the arts to cross certain boundaries and achieve healing, and help to foster tolerance in the world. So, we’re trying to get a sense of what those words really mean for people who come from different kinds of life experiences and worlds. Can you talk about your sense of those terms- tolerance and empathy, and what they mean to you?

Ruth Behar: So, what do the words tolerance and empathy mean? Those are really great questions. I can speak to the question in part from my own life story. There are two paths to tolerance and empathy in my life. One path is having been an immigrant and in particular an immigrant child. I think it is a very special position, to come to a new country as a child and to realize that you don’t fit in, that you have to work to fit in, -- that you have to work to belong; you have to learn a new language, a new culture, a new way of moving, a new way of acting.

*

I was five when I came from Cuba. We spent a year in Israel and then we settled in New York. I first had Spanish as my native language, then Hebrew for a year, and then English. That was complicated for a sensitive child, as I was, and then suddenly realizing that people thought I was dumb in my school in New York because I didn’t speak English. Experiencing this form of discrimination was painful. Now, I have a word for it, but I didn’t have a word for it as a child.

I remember, though, arriving in New York, where if you were Latino and you spoke Spanish and you were in Spanish Harlem, that was okay. But in other parts of New York, Spanish and being Latino was not so common as it is now. I remember going to restaurants where waiters did not want to serve us because we did not speak English properly.

Going through that feeling of being disempowered and then becoming more empowered by learning the language was a complex process, through which I learned the meaning of tolerance and empathy. I wanted people to have some empathy towards me as a child who couldn’t speak the language. Once you realize you need other people’s empathy, that’s how you develop your empathy for others. When I saw an immigrant child arriving after me, after I’d started to adapt, I knew that this new person in the classroom needed to be viewed with sympathy, -- viewed with empathy: “I’ve got to reach out to this person, because I remember being in this situation when I was the helpless one and I didn’t fit in.”

*

So that experience of not belonging I think can create an experience of empathy and tolerance, and it can create a foundation for empathy and tolerance to develop, and an understanding that this person is suffering and this person needs help. So, for me, the immigrant path was [important in] cultivating my heart, through that experience of having been an immigrant--of having been an outsider.

A Car Accident and the Importance of Helplessness

Ruth then continues to talk about the other path that helped shape her sense of empathy – a car accident that left her in a body cast for a year when she was 9½ years old. This is also the experience that inspired her to write her book, Lucky Broken Girl.

RB: That was of course a horrible experience. Any child would hate being in that situation. All of us hate being sick. So imagine being in bed, and unable to get up for a year and having to depend on your family to bring you a bedpan, to bring you your food. -- I think being wounded, going through an experience, again, of helplessness in a different kind of way -- an inability to walk, an inability to be mobile, an inability to be free -- were experiences that also helped to cultivate in me a sense of empathy and tolerance. I came to feel a connection with those who are wounded, with those who in any way struggle with their bodies.

We take for granted, those of us who are healthy, our good health, our mobility, all the things that allow us to function in our day-to-day lives. When I see others who are struggling with physical or other kinds of ailments, I want to help, my heart goes out to them. In childhood, I had these two paths to empathy.

*

Reading and Imagining Other Ways of Being

RB: And I think another path is books and reading. I think a lot of us learn empathy through reading... Because I was in bed for a year, I became a reader. I didn’t have much I could do – but I could escape from my bed by reading books.

Whether it was Nancy Drew mysteries, or just escapist books that I read, such as Robinson Crusoe, these books helped me travel inside my mind and through my imagination. Books are fantastic because you read about characters who are not you. You read about characters, or protagonists, that allow you to enter into other ways of being, other ways of thinking, other ways of being in the world. This also stretches you and cultivates empathy. Reading is central to the process of learning empathy.

Music and Tolerance

RB: Music is so important in my life, too. I love various kinds of music, and I love dance, also. My brother is a jazz musician. We grew up listening to the songs of Beny Moré and Celia Cruz and dancing the cha-cha-cha at bar mitzvahs. So music has always been a part of our lives. I studied violin and Spanish guitar, when I was young. I used to really love to play music. .... I think music opens up different parts of the soul. We need as human beings both those forms of communication that are verbal and those that are non-verbal. And music has that ability to cross bridges, to connect people in so many different ways. You can listen to a song in a language you don’t know and you can love it... That creates a kind of empathy as well – music can help you to understand another culture. ... That’s yet another way of thinking about empathy–whether it’s music with lyrics or not, music essentially takes you to another place – allows you to travel through your imagination.

Musicians can communicate across languages, just through sound. You put four musicians together who play salsa. And they don’t need to speak with each other. You get the percussion going, and they know what to do. They know the clave. They know the sound. And people can dance to the music without understanding the words of the songs. That’s so extraordinary, in terms of building lines of communication between people and creating tolerance. You might have a limited understanding of another culture, but you listen to the music of the people, and suddenly, something opens inside of you. You don’t have to be Argentine to cry when hearing Carlos Gardel sing with nostalgic sorrow of his lost city in “Mi Buenos Aires querido.” Music creates bridges of the heart, something we desperately need more of in these fraught times.

*Excerpts from a conversation recorded in Mexico City, July 3, 2017.

Images courtesy of Ruth Behar.